Why teams resist change

It’s fair to say that today’s businesses are facing higher levels of uncertainty and change than seen over the last 30 years or more. And whilst business leaders are certainly feeling it, the full impact of the change really sits with their teams; who are being asked to change not only the tyres but the oil and the headlights on an accelerating car over a pot-holed road.

In this, the first of two articles, I’ll explore some of the key influences (systemic and psychodynamic) leading to teams resisting change - including the social defence mechanisms in play and the negative team behaviours that result from them. In the next article I’ll then focus on how to create positive change culture in teams.

Firstly, I’m going to focus on what James Clear (of Atomic Habits fame) calls the Problem phase; why and how teams put up obstacles to change. And at this point, it’s always a good idea to check in with Kurt Lewin, the godfather of change theory, who neatly divided what he called ‘the restraining forces to change' into two questions:

1. What are they protecting?

2. What are they assuming?

When he talks about what the team are protecting, he’s referring to social defence mechanisms. These occur at both an individual level and also a group level. For the individual, you’ll probably be familiar with the defence of not putting your hand up in class (or at work!) even when you’re pretty sure you know the answer. This is a defence to being publicly shown up as not clever enough in the event you are wrong. The defence is a subconscious promise we make to protect ourselves from a negative experience.

Teams often 'park the bus' in response to anxiety

For the team faced with the uncertainty of change, we see a similar defence in the obstruction to changes to current roles, tasks or processes. It can be amazing, and frustrating, how rigidly a team can hold on to an old way of working, even after plenty of training sessions and clear demonstrations of the benefits of a new system – and often despite previous complaints about the old process.

This defence mechanism is rooted in anxiety:

anxiety over capability – do we have the knowledge and skills to work in this new way or to deliver this new task

anxiety over roles – will this new process affect our understanding of each other’s roles (the connected authority and politics)

anxiety over existence – does this change spell the end of the team (esp if technology is part of the change)

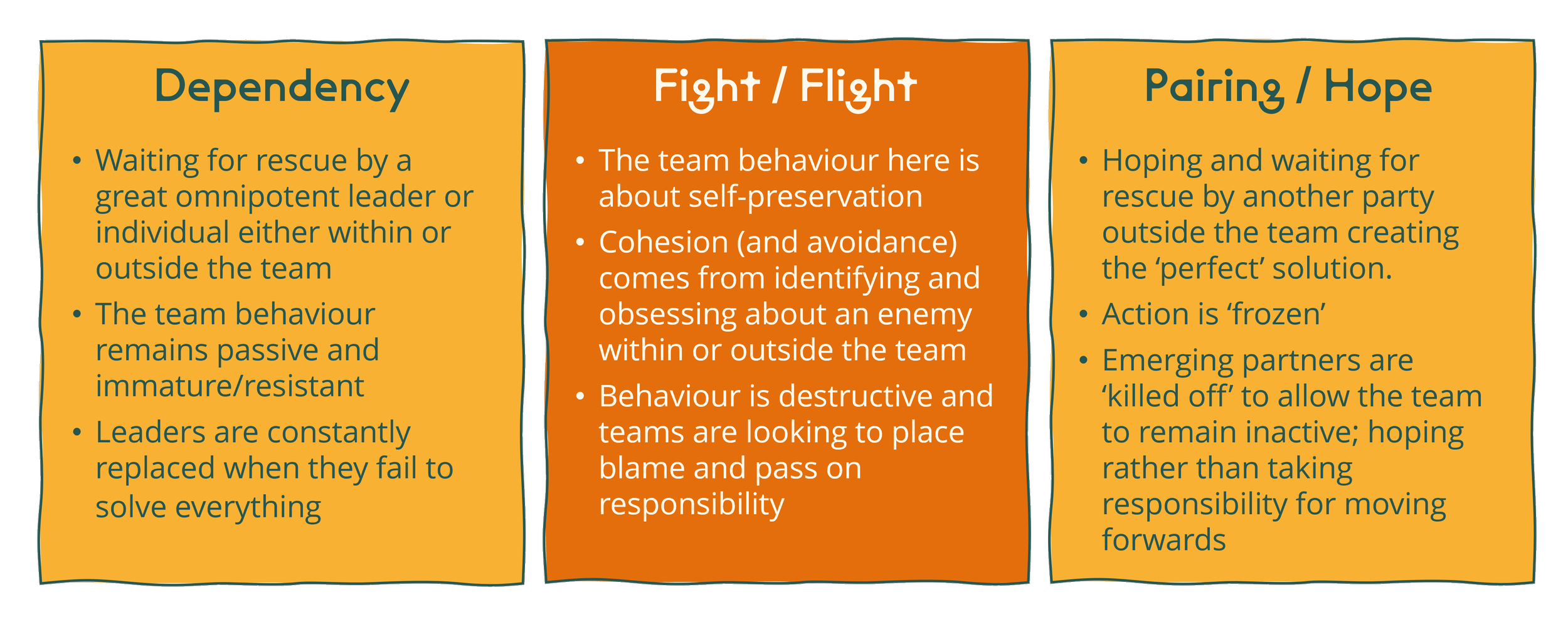

As a result of this, often unspoken, anxiety, teams can develop anti-task behaviours. Wilfred Bion defined 3 core behaviours or as he called them ‘basic assumptions’ because they stem from a collective assumption of what will protect and save the team from its own anxiety. And whilst teams tend to have a default assumption, it is far from unheard of for all three to be present in a single team.

Wilfred Bion's descriptions of group anti-task behaviours

It's important to note that a team can look very busy whilst caught up in anti-task behaviour – and actually one key indicator can be lots of team meetings but likely with no clear agendas and few if any outputs.

The final negative impact on team change to be aware of relates to the interaction between the task and the sentient boundaries (thanks here go to A.K. Rice). Hopefully the task boundary is relatively self-explanatory; defining the nature of the new output, changes to the resources required to deliver it, and any additional responsibility for its quality or performance. That’s the systemic stuff sorted, though clarity in this space is often wildly over-estimated by team leaders and managers.

But then we get into the messier psychodynamic or sentient boundary. This encompasses the team’s collective belief in the task, their sense of identity, purpose and motivation. The best team performance can often be linked to a clear overlap in a team's task and sentient boundaries – and teams that have existed and evolved over time tend to demonstrate this as the culture of the team develops around the task. But misalignment between the two can create significant challenges to a team’s psychological contracting to the new task, and resistance to the change.

So what have we learned? That there are both conscious and unconscious ways in which teams can resist change. And that the team has a sense of self-preservation in a similar way to individual people that results in behaviours that will reduce its ability to embrace change and, as the Navy SEALS label it, ‘get comfortable being uncomfortable’.

Navy SEALS train their people to 'Get comfortable being uncomfortable'

Next time we’ll explore how to help teams embrace a change mindset and not only manage but thrive in these uncertain times.